Transparency of Anti-Corruption and Anti-Money Laundering Policies, Investigations, Training, and

Whistleblowing in Major Banks in Hungary (Research Internship Report)

Short Summary

Corruption is one of the most serious global issues. While practitioners in private companies, civil society organizations, and international organizations have actively engaged in corruption-reduction efforts in Europe and beyond over the last few decades, these reforms have not been satisfactory. For example, 18 percent of Hungarian citizens “know someone who takes or has taken bribery”, while the Hungarian government is regularly criticized by both academics and civil society organizations for the state capture of public procurement. Regarding the banking sector, there is another serious issue, money laundering, on top of corruption and bribery. Globalization has enabled criminals to more easily launder money through placement, layering, and integration. According to the U.S. Department of State, Hungary’s “primarily cash-based economy and well-developed financial services industry make it attractive to foreign criminal organizations”. Evidently, both corruption and money laundering are serious issues in financial institutions in Europe, particularly in Hungary.

How to Fight against Corruption and Money Laundering

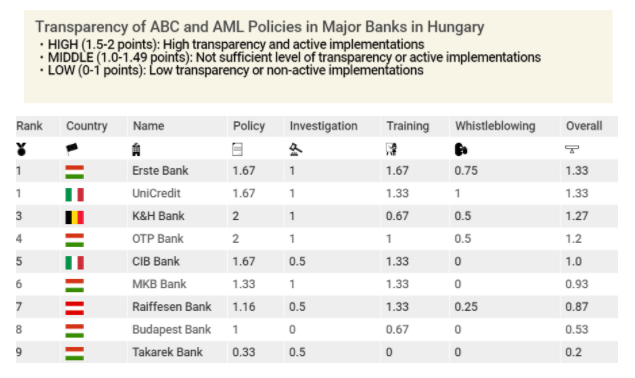

The literature on corruption and money laundering suggests that there are four key components for major banks in Hungary to consider in the fight against corruption and money laundering: clear and detailed relevant policies; strict and smooth internal and legal investigations; general and tailored training; and whistleblowing. This report evaluates the nine banks in Hungary with the greatest assets (based on the most recent market assessments): Budapest Bank, CIB Bank, Erste Bank, K&H Bank, MKB Bank, OTP Bank, Raiffeisen Bank, Takarek Bank, and UniCredit Bank. Fifteen questions about the four principles among these nine banks were scored as “High” (2 points), “Middle” (1 point), or “Low” (0 points). In terms of data collection, this report relied on publicly available sources from the banks’ English-language and local websites as well as Wolfsberg Questionnaires.

Findings: Score Comparison

The key results of scorings and discussions are:

- Although the average of overall scores for international banks with headquarters in other countries was slightly higher than for banks with headquarters in Hungary, the extent of transparency depends on each bank (as illustrated in the table of page 3): two Hungarian banks—Erste Bank and OTP Bank—scored relatively high while an international bank—Raiffeisen Bank—received low scores.

- The variance of scores among international banks is narrower than it is among Hungarian banks.

- Regarding the comparison among the four key components, while banks disclose their anti-corruption and/or anti-money laundering policies, they generally do not have sufficient whistleblowing procedures in place to ensure that there are incentive schemes to protect and support whistleblowers. (as illustrated in the figure of page 4; Red indicates the lowest average while blue indicates the highest average).

Findings: Nuanced Differences between the Banks

Also, three further differences were revealed.

- First, there are differences in the international standards/guidelines on which the banks’ policies are based. However, there is no evidence from the comparison that any of these particular international standards/guidelines help more than others. It is likely more important to simply follow a body of international standards/guidelines than it is to follow any specific one.

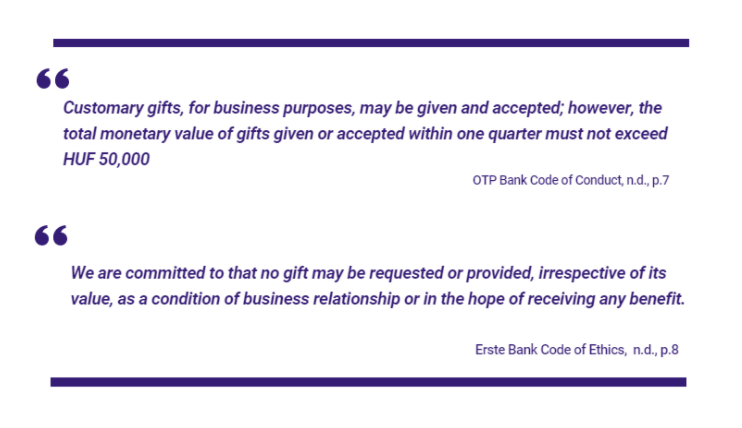

- Second, regarding the procedures on gifts and hospitality, few companies require the outright rejection of all gifts and hospitality. Rather, most of the companies that scored “high” just specify the threshold per party per year (see the citations below).

- Third, while most of the companies with a “high” score merely specify which area companies take as a risk, some companies disclose more information on the risk assessment. The comparison of these companies suggests that their focuses are slightly different: some focus more on country risk while others consider more factors as risk factors.

Findings: Additional Research

Additional research was also conducted through a Skype interview to understand the differences between published information and internal information. The key findings from this interview are as follows:

- Banks’ internal anti-corruption and anti-money laundering policies/procedures are more detailed than their public policies/procedures.

- The amount and extent of anti-money laundering training programs may differ from those of anti-corruption training programs due, in part, to differences in national legal requirements.

- In contrast to Western European countries, whistleblowing is not a common practice in Hungary due to its communist background.

Recommendations

- Publish internal anti-corruption and anti-money laundering policies/procedures to the public in order to enhance transparency.

- Improve the quality of internal investigations through frequent reviews and enhance cooperation with law enforcement by clarifying the government’s responsibilities.

- Improve the quality of compliance training through frequent reviews, periodic training, and tailored programs.

- Provide multiple whistleblowing channels.

- Ensure the protection of and non-retaliation against whistleblowers through anonymous surveys or other clearly stated means.

- Ensure that companies support and protect employees who refuse to act unethically.

- Introduce incentive schemes to promote ethical behavior and discourage corrupt activities.

The author of this summary and the report is Yusuke Ishikawa, former intern of Transparency International Hungary.

Both this summary and the full report are available by downloading the relevant PDF document at the bottom of this page.